THE ALBAN BERG PROJECT

Music in Transition

Since my undergraduate days I’ve been intrigued by the concept of “music in transition.” It seems a straightforward idea on the surface: Monteverdi, C.P.E. Bach, and Schubert all fall, chronologically and stylistically, between what generally are considered the main epochs of Western music. But things are not so simple. In the first place, music is always evolving: it’s with hindsight that historians identify periods of supposed stylistic stability. Furthermore, a living composer will naturally view herself as modern, there being for her no future period that her music may later be understood to anticipate.

But hindsight is the natural mode of the historian, and even if there is no such thing as absolute stylistic stability, there are periods of relative calm. As well, there as moments of upheaval (often encompassing not only music but literature, the visual arts, and culture generally) when we find a marked emphasis on innovation, sometimes side by side with a sense of decadence: from the throes of a dying world something new can be glimpsed emerging from the shadows.

A particularly dramatic example of such a moment is afforded by the period that marks the end of Romanticism and the beginning of Modernism. In Germany in particular, the years 1900 - 1911 mark a phase of intense experimentation; the period is dominated by the imposing figure of Arnold Schoenberg. (It seems necessary, in discussing the music of Alban Berg - particularly the early works - to begin with his teacher.) Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony, opus 9, completed in 1906, is generally considered a prime example of music in transition. An ambitious, Janus-faced piece, it sums up the stylistic features of the previous century while heralding an age to come. Like the grand B minor Sonata of Franz Liszt, it is cast as one movement, managing to suggest an overarching sonata-allegro form while also possessing the kind of radical changes of character usually associated with a multi-movement work - such procedures have precedent in the symphonic poems of Liszt and Richard Strauss, but the Schoenberg Chamber Symphony differs from them in being non-programmatic. The methods of thematic development owe something to Brahms; the chromaticism and dissonance are post-Wagnerian.

It is in the realm of texture and harmony that Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony breaks new ground. The work is contrapuntal to a degree seldom found since the fugues of J. S. Bach; Schoenberg’s unique, chamber-like ensemble is better suited to the articulation of this music than the grand orchestras employed by Bruckner and Mahler (to say nothing of Schoenberg’s own lush Gurrelieder, begun some years prior to the Chamber Symphony). The polyphonic lines are not simply melodic but motivically charged as well. This does not imply (as some have claimed is true of the composer’s later, atonal works) an indifference to the vertical dimension of sound, but it does invite an increased level of dissonance.

Specifically, the Chamber Symphony exhibits three distinct types of harmony in constant alternation: rooted, consonant triads, whole-tone aggregates, and quartal constructions. The first of these is responsible for what tonal aspects of the work can be found; the latter two, thanks to their symmetrical constructions, fail to project any chord roots, rendering those glimmers of key provided by the consonant triads paradoxically both fleeting and crucial to the formal design.

It is ironic, and very much in keeping with Schoenberg’s self-assessment as “a conservative forced by historical circumstances to appear radical” that, upon completing the Chamber Symphony, the composer felt a sense of satisfaction, having arrived at what he considered a mature style that would mark the beginning of a period of creative stability. In fact, as is well known, the expansion of tonality led to its demise in Schoenberg’s subsequent works, along with the complete emancipation of dissonance. So it is that we now view this work as exemplifying “music in transition.”

—--------------------------------------------------------------

While Schoenberg was working on the Chamber Symphony, his student, Alban Berg, was following the master’s footsteps. Berg’s opus 1, a single-movement piano sonata, completed in 1908, thus is modeled on Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, and features an overarching sonata-allegro form that seeks to contain a near-Expressionist emotional volatility while employing a technique of subtly continuous development. The Berg Sonata (a piece lauded by Glenn Gould as equal in quality to anything the composer would later write) is remarkable for its contrapuntal density. Employing a harmonic language similar to that of the Chamber Symphony, it brings the crisis of tonality to a kind of tragic climax, as the quartal harmonies, the whole-tone cascades, and the generally pervasive chromaticism and dissonance threaten to overwhelm the tenuously articulated key of B minor. Impressively for such a young musician, Berg here sums up a century of Romantic practice while presciently forecasting the Modernist movement: we sense, beneath the decay, the emergence of something crystalline, implacable, and gnomic.

The Summer of 1975

Half a century ago I worked one summer as a teller for the Harlem Savings Bank of New York, in order to cover the tuition for what would be my sophomore year at the Manhattan School of Music. It was during the previous Spring, while browsing in the school library, that I discovered the Berg Sonata; I quickly resolved to study and to practice the piece in what time was left to me in the summer, after work. I remember reading with fascination Gould's quasi-cyclic view of music history on the liner notes of an LP - “Here,” the pianist wrote (speaking of the Berg Sonata), “is tonality, betrayed and inundated by the chromaticism that gave it birth.” So great was my enthusiasm for this music that, in late August, I allowed myself to be persuaded, against my better judgment, to perform the piece on the occasion of a bank tellers’ party: as Berg’s dissonance relentlessly destroyed tonality I (like Kreisler in E.T.A. Hoffman’s story, who plays Bach’s sublime Goldberg Variations at a salon, systematically clearing the room) - I, with equal ruthlessness, ruined the evening’s mood.

But while the success of the piece varies with the expectations of its audiences, its attraction for me has proved lasting: the work has long been a staple of my teaching. I offer its extravagences to wide-eyed undergraduates, and probe its intricacies each Spring in the Doctoral seminar.

Creating an orchestral version

I’m not sure why it has taken all this time for the thought to occur to me which, once formulated, seems so natural - the thought of taking this pianistically difficult, highly contrapuntal piece and arranging it for an ensemble. Perhaps it’s because there is to much German music a purity bordering on abstraction, a near-disdain for the coloristic surface, the priorities having to do with structure and harmony/counterpoint. (I realize this statement is contradicted by several fantastically colored works by both Berg and Schoenberg.) In fact the Berg Sonata has been arranged for full orchestra by Theo Verbey; it has also been arranged for string quartet.

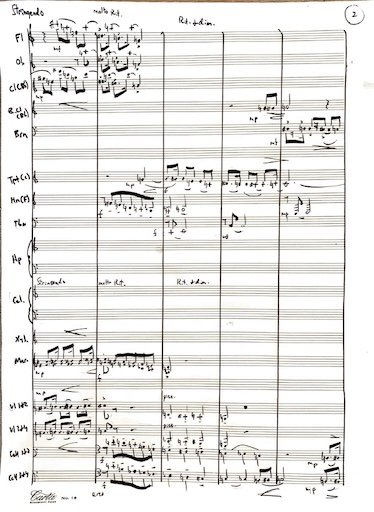

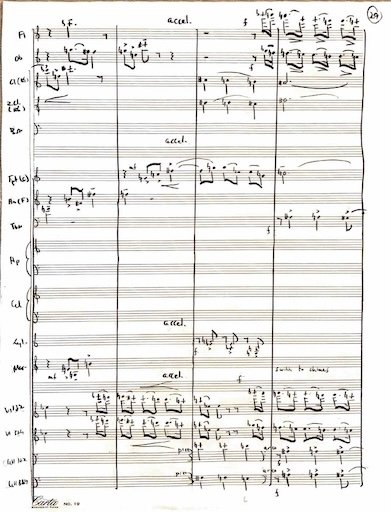

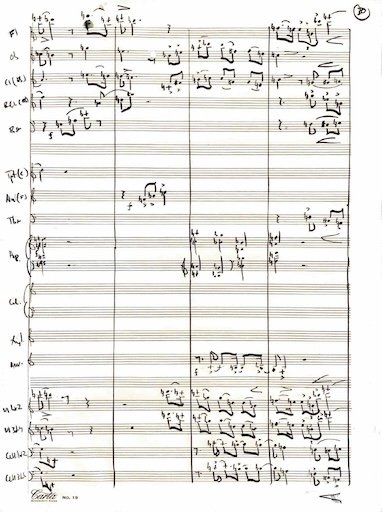

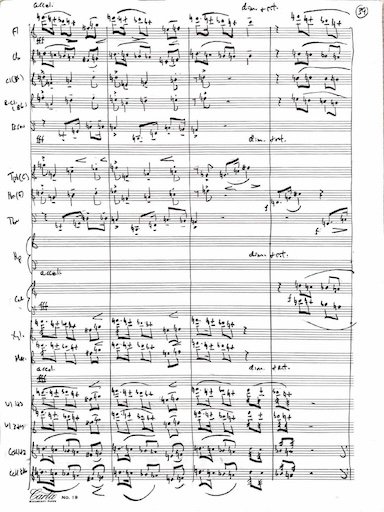

My choice has been to follow, though not precisely, the model provided by Schoenberg, and to employ a chamber orchestra. I made this decision not from a desire to imitate or draw parallels, but organically, as I imagine Schoenberg did: the interplay of supple, moving lines would get bogged down in heavy string vibrato; preferable is an agile, kaleidoscopic ensemble.

Of course, this changes the work fundamentally (though I’ve altered not a single pitch) - from a black and white sketch to a vibrantly colored fresco, from a network of Platonic ideas (fraught with Freudian overtones) to a sensuously textured fabric. And this I did, I must admit, with certain reservations: in its original form, the Berg Sonata presents to the listener a procession of themes in constant transformation in such a manner that, as in a dream, each new motif strikes us both as strange and as familiar. These compelling relationships are accomplished by the young genius composer primarily through alterations in rhythm, register, dynamics, and pitch-order, applied to an unprecedentedly strict unity of interval-collections. It is my fear that, through orchestrating the piece, in some cases I have unintentionally suggested similarities among musical ideas while, in other cases, unintentionally obscured relations that were clearer in the piano version. Oh well!

In transcribing from piano to chamber orchestra I found two considerations to be of paramount importance: rhythm and balance. With regard to rhythm it should be said that the piano has two acoustic qualities that distinguish it from orchestral instruments generally: a percussive attack and a relatively rapid decay. I do not intend to suggest that the Berg Sonata is a particularly percussive work - quite the contrary: with its ubiquitous rubato and frequent phrasing over the barline it presents a very fluid sense of time. But this is not to say the downbeats are irrelevant: the effectiveness of hemiola effects (in Beethoven and Brahms, in Schoenberg and Berg) is premised on a perceptible conflict between the predictable downbeat accents of a steady meter and the shifting offbeat accents of the musical phrasing. The pianist, without overdoing it, can always create (with dynamics, agogics, or pedaling) a subtle sense of downbeat while at the same time, through crescendo and diminuendo effects, express the syncopated contours of the music. But orchestrally (particularly for the strings) this is more difficult, and the result may be that, when the melody phrases over the bar, all sense of meter is lost. To address this danger I took, in the first place, the liberty of altering the bowing and slurring where needed, in order to articulate downbeats.

Also in the interest of rhythmic clarity I made two other decisions: to employ both pizzicato (mostly in the bass register) along with the harp in order to punctuate downbeats, and to utilize the xylophone and marimba - not primarily to make the ensemble more colorful (though that’s fine) but to capitalize on the ability of those instruments nimbly to articulate those passages with triplet sixteenths and awkward leaps.

As for the issue of balance, it is the unique quality of decay that the piano possesses which conditioned, to a large extent, my choices of timbres and doublings. In fact, the Berg Sonata exhibits two distinct textures, each requiring a separate response. The first texture (less common than the second in this work) is melody with accompaniment, a texture found in various forms through the Classical and Romantic eras. Without needing directions from the composer, the pianist knows to create a hierarchy of dynamics according to which, in some proportion, melody is strongest, bass is second, and middle voice “fillers” are softest. Orchestrally, this is the job of the composer or arranger more than the conductor. So I was careful to score the inner lines more lightly than the outer ones. In this context the pizzicatos and harp-plucks, with their accents and rapid decays, were felicitous.

But the majority of the sonata, as I have mentioned, is contrapuntal - indeed it was this very aspect of the piece that originally provoked my desire to render it for numerous melodic instruments. One might assume that, for this kind of texture, an approximately equal dynamic would be appropriate for all parts, and this is sometimes what I chose to create. But a careful examination of the score reveals that, while most of the musical substance is linear, not all of it is thematically significant. The intense, unrelenting drama is often expressed through rising and (especially) falling chromatic lines: these are crucial to the pathetic affect of the work, but melodically they are of less interest than the soaring and sighing gestures that course through them like fish in a dark and turbulent sea. If the sliding chromatic lines were given equal prominence to the thematic ideas, a shapeless chaos would result, in which the rational side of the music would be drowned in pure pathos. Again, the discerning pianist would voice each passage appropriately, allowing the themes to stand out, in some measure, against the sliding background (much as one might interpret a fugue, placing statements of the subject in relief against supporting lines), while - again - in an orchestral transcription, this is the duty of the arranger more than the conductor. In such passages, then, I have attempted to create, in each instance, a balance requisite to the thematic import of the moment.

Music Out of Time

Somewhere in the middle of the task described above, it occurred to me that Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, so crucial to my arrangement of Berg’s sonata, is properly called Chamber Symphony No. 1 - which means there must be a Chamber Symphony No. 2. Does anyone know this piece? I didn’t, but I have recently made its acquaintance and, as with so many things one encounters after a lifetime in music, that acquaintance has provoked thoughts and suggested connections to myriad other musical works and historical facts, while prompting philosophical ruminations as well.

The Second Chamber Symphony was begun immediately after the completion of the first, but abandoned unfinished in 1908 (?). Some thirty years later Schoenberg returned to the piece, a changed man in a different world. The great atonal experiment (which became the great experiment in serial music) made the language of the Chamber Symphony old-fashioned rather than forward-looking; this musical upheaval had its dark corollary in two World Wars.

Schoenberg explained his decision to return to his long-neglected work as instigated by what he felt were “unexplored possibilities” of the tonal system; listening to this peculiar work, I would say his intuition was right: the Second Chamber Symphony does not sound quite like anything else - except, to some degree, the First Chamber Symphony. And this is unfortunate because, despite many remarkable touches, it is, I fear, not nearly as successful as its predecessor.

Whose fault is this? Should we blame Schoenberg (because you can’t turn back the clock, because the inspiration of youth cannot be recaptured)? Or the Nazis (because in the aftermath of the Holocaust it is impossible anymore to believe in the ideals upon which Romanticism was built, and if you don’t believe in beauty and love you can neither convincingly express it nor be persuaded by its appearance)? Or does the problem lie with us (because as listeners we know too much - I wonder: if I knew less would I hear this music differently? We tend to assume that we respond to music simply as sound - if we like it, it’s good. The Second Chamber Symphony can demonstrate that our reactions are conditioned by our knowledge (or ignorance) of extra-musical factors. If I thought that the Second Chamber Symphony was written first, and completed at the beginning of the 20th c., a time of artistic optimism, would I accept it more readily, understand it differently? Do my reservations regarding the work’s inspiration and beauty stem not from its inherent qualities as much as from a feeling of discord between the historical moment of its completion and the world-view it expresses? Tainted as I am by what I know, I find it impossible to answer these questions.)

What I can aver is that the Second Chamber Symphony is an early example of what subsequently becomes a rather common phenomenon - what might be called “music out of time.” To the innocent listener, the Adagio from George Rochberg’s Third Quartet (an example from the second half of the 20th c.) sounds like an unknown treasure from Beethoven’s final period; to the listener aware of its provenance it may seem more like a musical Frankenstein, staggering out from the graveyard of music history, at which we cower in dismay, crying, “Get back! Thou hast no place here!” (The reader will forgive this hyper-emotional reaction, considering my recent and intense immersion in the Expressionist sea of Berg’s Piano Sonata.) Other examples of “music out of time” are the late works of Richard Strauss and my own adventures in the alternate universe 19th c. Of Heinrich von Ofterdingen.

But the Berg Piano Sonata, for me, will always be timely. Indeed, my work on its orchestration brings me full circle, connecting me in a meaningful way to my own artistic beginnings, as the wide-eyed youth comes face to face with his later self - wizened but wiser and - to paraphrase Glenn Gould - inundated (but not betrayed!) by the chromaticism that gave birth to his musical curiosity.